#NEW THE MASTER COOK & THE MAIDEN

Vengeance…or love? Will Alfwen have to choose between them? And what part will the handsome Master Cook, Swein, play in her life?

https://amazon.com/dp/B088RJNYJ4/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=lindsay+The+master+cook+and+the+maiden&qid=1589871083&s=digital-text&sr=1-1…

UK https://amazon.co.uk/dp/B088RJNYJ4/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=The+master+cook+and+the+maiden&qid=1589871416&s=books&sr=1-1…

#Romance #MedievalRomance #RomanceNovel

THE MASTER COOK AND THE MAIDEN

Vengeance…or love? Will Alfwen have to choose between them? And what part will the handsome Master Cook, Swein, play in her

life?

UK

https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B088RJNYJ4/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=The+master+cook+and+the+maiden&qid=1589871416&s=books&sr=1-1

Romance, MedievalRomance, RomanceNovel

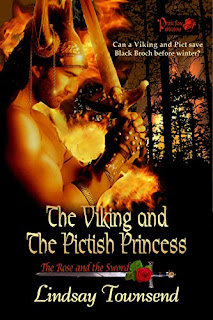

The Rose and the Sword Novel Series

Excerpt

The Master Cook and the Maiden

Lindsay Townsend

Third day of Lent, 1303

The small brown dog stumbled towards Alfwen as she pounded washing in

the river. Without stopping her work she watched the little rough-coated

creature slip through a gap in the convent boundary wall to limp her way,

flopping down on the damp grass twice before it reached her.

“Hey, boy,” she whispered, glad of the honest companionship even if it

was just a dog. Hearing a pitiful whine she dropped the dry crust she had been

saving for her supper in front of the shivering beast. “Go on, it is yours.”

The scrap disappeared between the dog’s narrow jaws. Alfwen wiped a

hunger tear from her face, glancing about. So far, she and the little dog were

safe from discovery. This close to Terce, the other nuns and novitiates of the

convent were busy with their own assigned labours. As Alfwen had pretended she

was afraid of the river, naturally the spiteful Mother Superior had ordered the

girl to do the sisters’ laundry, an outdoor task that suited Alfwen very well,

even on this bitter afternoon in early spring. Tempers sharpened during Lent,

when all were famished, and to be in the fresh, chill air was better than being

mewed up in the sooty church or cramped, icy scriptorium.

Kneeling on the riverbank, Alfwen wrung out another section of bedsheet

and dunked the next, flinching at the freezing water flowing over her reddened

fingers and pale skinny arms. No possible spy was with her, no religious or lay

brother or sister, and she could relax a moment. She unwound from her knees and

sat on the grass, trying to ignore the burning prickling in her legs. When no

shout or complaint issued from the convent she stroked the dog.

With a soft whine the beast crawled closer. So small and trembling, she

thought, and she could count its ribs through that rough brown coat and the raw

patches along one flank where the fur had shed. Recalling a lively, bouncing

pup from long ago, she whispered, “Teazel?”

The dog weakly wagged a balding tail. As it raised its head, Alfwen

spotted a filthy cloth collar, half-hidden by dirt.

“I gave you to Walter with a leather collar,” she murmured, surprised

she remembered that detail. Teazel snuffled and edged even nearer, so she could

see the grey in his muzzle. She wrapped the dog in the rest of the dry sheet

she had yet to scrub and fought down a wave of horror.

Walter must be dead. Teazel would never have left him.

She tried to pray for her brother. Failing that, she tried to remember

him. It had been seven, no eight years since Walter and his new wife had

abandoned her in the convent, though Alfwen knew she had no vocation.

I was ten years old and my parents had just died.

Walter was in the first flush of marriage and lordship and his wife—Alfwen shuddered, checked again for spies and

admitted the truth. Enid hated me.

A growl came from the tangled sheet as if Teazel agreed with her. A

quivering, questing muzzle emerged from the heavy linen and Alfwen was struck

by a memory of Walter. Her older brother, whirling about the tilting yard with

his new puppy in his arms, laughing as the little dog yapped and squirmed and

nuzzled closer.

“He likes me!” Walter cried, pressing a sloppy kiss on the pup’s back.

“He is yours,” Alfwen agreed, and Walter had grinned at her, his hazel

eyes bright with joy, the sunlight picking out the red glints in his brown

curls.

Enid had soon shorn off his hair, claiming it unseemly for a young lord.

Alfwen had scowled and Walter had scolded her for protesting against his wife,

although she had said nothing. Two days later she was delivered to the convent,

a poor, mean place. My limbo, with an

entrance to hell, and my brother did not care, did not question. Eight

years she had been here as a novitiate, neither lay nor nun. Postulants to a

religious life were supposed to serve only a year as a novice but as a sister

Alfwen would have status and Enid and the Mother Superior between them did not

want that. Instead I am trapped and my

close family have forgotten or dismissed me. Would I be as stupid and selfish in wedlock as Walter?

Alfwen shook her head and tried a second time to pray for her brother’s

soul.

He is gone forever and I cannot even cry.

She tried to think of him, remember him, kindly memories. Save for when

she had given him Teazel, and he had taught her to write her name, she drew a

blank on any more joyful times. Have I

forgotten or was Walter really so morose and carping? Am I unjust in how I

consider him now?

In the dank grey light of early spring, the bell for Terce rang through

her like a blow. Numb, Alfwen rose, ready to gather her work and stumble into

the nunnery’s huddled church set close to an expanse of marsh but out of reach

of the river. She reached for the part-washed, part-dry sheet and Teazel burst

from its coils. Again she noted his thinness, the scrap of cloth collar.

The collar was once part of a favourite gown of mine,

a yellow dress my mother made me.

The bell for Terce continued to toll and Alfwen detested its sweet

intrusion.

Anger sharpened her, tempered her dull acceptance of convent life into

more than resentment. In a blast of sudden added colour she saw the white and

pink daisies by her feet, the blue glow of a kingfisher farther down the

riverbank, the glint of gold amidst the dirty yellow of Teazel’s collar.

He has something pinned to his collar.

A shadow fell across Alfwen before she could unpin the tiny roll of

parchment, but thankfully it was merely a cloud, not a nun coming to drag her

to service.

No, the good sisters of Saint Hilda’s will be

hastening to church. I will not be missed until after the latest holy office.

Alfwen flinched as the gold brooch scratched her fingers and then the

thing was undone. Heart hammering, she smoothed out the parchment.

Two words only in her brother’s hand, but a message to her, all the

same.

“Avenge me.”

Chapter 2

Swein saw the girl drop into the water from the riverbank and leapt from

his waggon, sprinting to reach her before she drowned. Hearing no splash or

screams he dared to hope and ran faster, forcing air into his searing lungs.

Pounding along the track and over the water-meadow he vaulted the mud

brick wall of the convent. He landed clumsily but kept going, determined to

save her. Never a fatal accident in my

kitchen and I’ll not gave one here, either.

Scrambling to the edge of the bank he stared downstream, seeing nothing

but a young trout, swung round to scour upstream—and choked on his breath.

Tripping daintily over the river pebbles at the stream’s edge the girl walked

steadily away from her pile of laundry.

Swein flattened himself to the grass and watched the small, skinny

wench. Her skirts were sodden to the backs of her knees, he reckoned, but she

moved smoothly, never looking back. Across her retreating shoulders she carried

a sling, made from part of a sheet. A little old dog poked its muzzle from the

bundle and seemed content with the ride.

A runaway from Saint Hilda’s. “No business of mine,” Swein muttered, but his ankle

ached so he lay still and stared.

The girl disappeared round the bend in the beck—stream, Swein mentally

corrected, since this was in the south, not north—her presence winking out like

a small star.

She will walk to the ford and take the Roman road

hence. I could drive my waggon there and wait for her.

“Why not?” Swein said aloud, flexing his toes in his boots. “I have no

business with Saint Hilda’s.” The head nun in the place did not like men and

detested cooks so he had never had cause to visit in his travels.

‘Tis Lent and I go home for Lent. Cooking food for

fasting times does not stir me and my folk are waiting. He had the early gifts ready for them.

Still he would catch Nutmeg, his mule, and his waggon and drive to the ford.

That girl needs fattening up, I reckon,

fleeing from Saint Hilda’s.

The

nobles I cook for do not like me curious but I am my own master and this Lent

time is my holiday.

He could do largely as he pleased and he wanted to see the lass’s face.

Swein rolled to his feet and set off back for the

track, whistling a merry tune.

****

Alfwen glanced at the sinking sun and the crossroads

with dismantled archery butts stacked against the oak tree. She had hoped for a

hiring gather and had her story ready. I

am a laundress seeking honest work.

She wanted to steal a nag and ride to her family’s

seat at Ormsfeld, but she brutally dismissed the desire. She needed to know how

Walter had died and who were his enemies. Teazel

would never have left if Walter lived still. Yet no one had come to the

convent to tell her that her brother had died. Although I am a de Harne I

have been buried at Saint Hilda’s for eight years and no doubt forgotten.

“Avenge me,” Walter growled in her head, in a voice

she was not sure was his, or what she remembered of him.

Again she was relieved she had not taken final vows.

Nuns were not supposed to plot vengeance.

Why

should I? When did Walter care for me?

Alfwen squashed such thoughts, stamping her feet in a futile

bid to keep warm. Her skirts and sandals were still wet from the river and she

knew she would look strange, a lone woman with no protectors. I dare not linger here past twilight. I have

to find shelter, food for Teazel.

The dog slept on the damp ground in her rough bundle,

weary with hunger. Enid starved him. Did

she do the same cruel thing with Walter?

“Are you seeking work?”

Startled, Alfwen turned, stumbling as she took a rapid

backwards step. The man looming over her was so big—

Strong arms caught her, brought her safe against a

broad chest.

“Here,” said the stranger as she gulped in breath to

fight, “Before you hunger faint.”

A large calloused hand pressed a warm round dumpling

into her palm, a white plump dumpling straight from a pottage pot, but not so

hot as to burn. The comforting heat and yeasty scent took her straight back to

childhood, pottering after Simon, the old cook, who would often take her with

him into the kitchen garden and let her eat fresh bread from his ovens.

Avenge

me, Walter scolded,

while she chewed and swallowed the dumpling treat, licking her fingers after.

“I need a washer lass,” the stranger went on, dropping

a morsel of something on the earth for Teazel. “I feed my folk well. You come?”

He almost had her at feed well, but Alfwen had not

sprung the trap of the convent to fall into another. She shook her head. “I

cannot stay, sir.”

Now she spoke, Alfwen felt the light-headedness of

hunger boil into the seethe of panic. What

might this big brute make me do for his food?